Use of analytics cookies on digital services is governed by the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR), which state that analytics cookies may only be stored in users’ browsers if they have explicitly opted in to this. Analytics cookies are important to us because they allow Google Analytics to identify who a user is, even if they are returning to a site later in time. In general, the more users that opt in to cookies, the more we can track, and so the more useful the data gathered is.

Although we now have a cookieless analytical platform based in BigQuery, Google Analytics remains useful because of particular capabilities it has around funnel analysis, tracking particular types of frontend events (e.g. scroll depth) and handling particular types of marketing/SEO data (e.g. from Google Search Console). It is also possible that in future we may want to introduce other forms of analytics tooling that also rely on cookies.

We A:B tested a range of cookie opt-in banners on our service, including ones based on the gov.uk design pattern. These findings were shared with government more widely on Github so that they can help inform future iterations of the official design pattern and help to set expectations of cookie opt-in rates for other services.

The designs included displaying no banner at all, banners with and without an explicit ‘Reject analytics cookies’ button, banners placed at the top and bottom of the screen, banners with different background colours, and a full screen modal design that required users to make a choice about their cookie preferences to be able to see the site. A sample is shown at the bottom of this post.

# Hypothesis

If we make the cookie opt-in banner more intrusive, we can increase the cookie opt-in rate without increasing the bounce rate or decreasing the site search, vacancy view or account creation rates significantly.

# Who we tested with

We carried out 2 rounds of testing with a total of 254,756 users, and evaluated the cookie opt-in rate alongside indicators of user engagement and task success (bounce rate, site search rate, vacancy view rate and jobseeker account creation rate) for 6 different cookie opt-in banner design variants in each round of testing. Findings from the first round of testing informed the designs that we tested in the second round.

# Findings

Our key findings were as follows:

- All the cookie opt-in banners had a very similar bounce rate, site search rate, vacancy view rate and jobseeker account creation rate. Only slight variations in these rates were detected. They were also very similar when no cookie opt-in banner was displayed at all. So, we think that the cookie opt-in banner had little to no impact on users’ perception of the relevance of the site to them, or on how likely they were to interact with the service.

- It was very rare for users who bounced to choose to opt-in to analytics cookies. Even when required to make a choice about their cookie preferences, around half of users bounced before making that choice, and so would not be tracked in a cookie-based analytics tool. (Note - we counted a user as having ‘bounced’ if, on that date, they only viewed the page that they initially landed on, the cookie opt-in banner and/or the cookies preference screen)

- The GDS design pattern, which offered an explicit ‘reject analytics cookies’ button alongside an ‘accept analytics cookies’ button, had a higher cookie opt-in rate than our previous banner design, which required users to click a link to a separate screen to choose to opt out of analytics cookies. 29% of non-bouncing users opted in when presented with the GDS design pattern, compared to 25% when presented with our previous banner design. These figures rose to 33% and 26% in the second round of testing. The makeup of our user base varies substantially throughout the academic year, so this variation did not surprise us. A possible explanation for this would be that the GDS design pattern takes up more space on a mobile device than our previous design pattern, because of the space taken up by the explicit ‘reject’ button and one line of additional explanatory content.

- When users were required to make a choice about their cookie preferences to view the site, either through an ‘accept’ button or by setting a preference on a separate page, 98% of non-bouncing users chose to opt-in to analytics cookies. However, despite this, we chose not to implement this opt-in banner, because we had limited evidence from the other goal conversion rates evaluated that users were behaving in the same way as if no opt-in banner had been displayed at all. We had some - albeit limited - quantitative basis for the belief that this design discouraged users from making a considered choice about their cookie preferences.

- The background colour of opt-in banners made little or no difference to the cookie opt-in rate.

- The placement and stickiness of opt-in banners made a significant difference to the cookie opt-in rate. Making the GDS design pattern ‘sticky’ (so that it remains on the screen even when the user scrolls down) increased the number of non-bouncing users who opted in to analytics cookies from 33% to 53% in the second round of testing. Placing the banner at the bottom of the screen instead of at the top increased this further to 68% of non-bouncing users. Including users who bounced, these figures were 16%, 26% and 33% respectively.

- The cookie opt-in rate varied significantly by device. For example, the GDS design pattern had an opt-in rate of 56% of non-bouncing users on mobile devices, but only 24% on desktop. When the banner was made sticky, these figures went up to 65% and 30%, and when the banner was positioned at the bottom, they went up further to 78% and 47% respectively. We think this is likely because a cookie opt-in banner takes up proportionately more screen space on a mobile device than on a desktop device. This is particularly true of our user base, who often use iPhones with smaller screen sizes.

- The difference in opt-in rates between mobile and desktop introduced a significant skew to data gathered in cookie-based analytics tools that could lead service teams to draw invalid conclusions if they are not conscious of this bias. For example, during the second round of testing, 28% of Teaching Vacancies users were on desktop devices, while 72% were on mobile devices. However, if these figures had been calculated using a cookie-based analytics tool (like Google Analytics) then, without accounting for the bias, we would have concluded that only 14% of users were on desktop, and that 86% were on mobile devices. This would have been a 50% underestimate of the proportion of desktop users. To illustrate the impact this skew might have for our service, this could have led us to over-prioritise mobile support in our design and over-prioritise mobile users in user research, which would effectively have given desktop users less of a voice.

- Users showed a strong preference for accepting analytics cookies over rejecting them - for this design pattern, in the second round of testing, only 2.6% of non-bouncing users explicitly clicked the ‘Reject analytics cookies’ button. This number rose to 5.3% if the banner was made sticky, and 6.5% if the banner was moved to the bottom of the screen.

# Screenshots

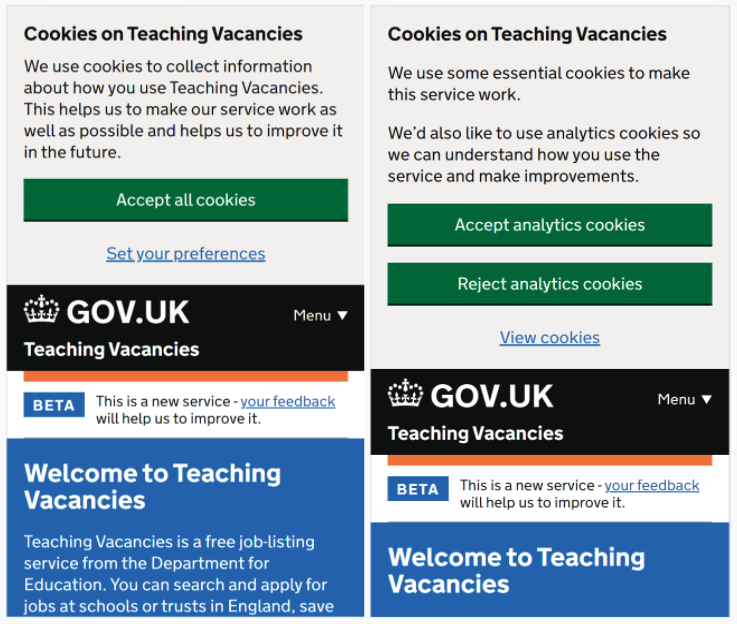

Our original banner, and the new GDS design pattern we also tested:

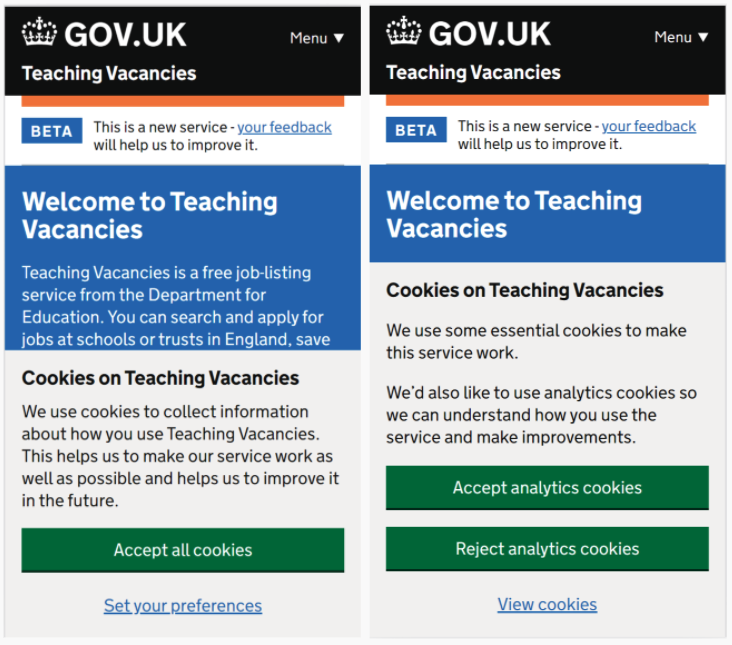

The same banners, positioned at the bottom of the page - these had higher opt-in rates than when positioned at the top of the page:

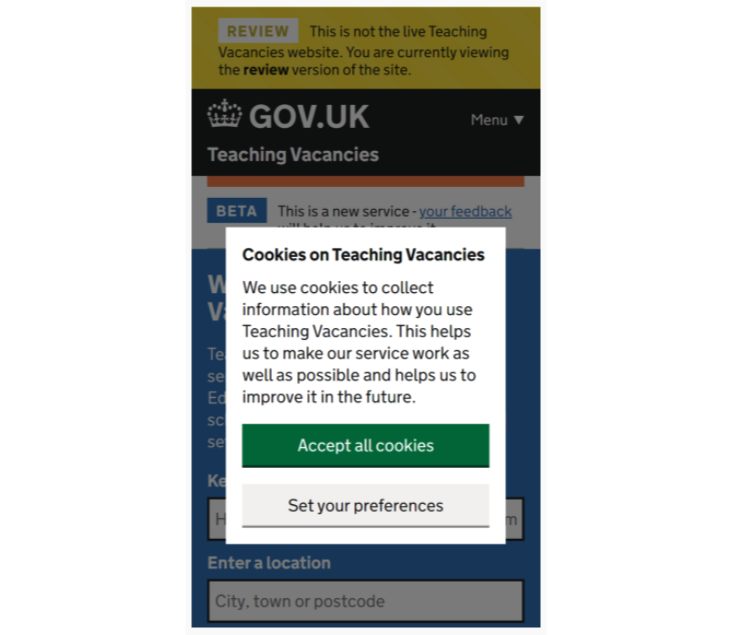

The ‘modal’ banner we also tested:

# Next steps

We decided to implement the GDS design pattern, but positioned at the bottom of the screen, because it maximised the opt-in rate, minimised the skew, showed no quantitative evidence of reducing user engagement with the service and ensured that users were able to make a clear choice about their cookie preferences.